I read The Madman of Piney Woods, the latest book by Christopher Paul Curtis, this fall because I am working on a novel with two protagonists and I wanted to study how a real master of the craft handled the inherent difficulties in dual narration. But I become distracted from my initial goal by the story of Alvin “Red” Stockard. If you are looking for a more traditional review, this book got starred reviews at both the Hornbook and Kirkus. I’m going to take a look at the story from the perspective of cultural authenticity.

I read The Madman of Piney Woods, the latest book by Christopher Paul Curtis, this fall because I am working on a novel with two protagonists and I wanted to study how a real master of the craft handled the inherent difficulties in dual narration. But I become distracted from my initial goal by the story of Alvin “Red” Stockard. If you are looking for a more traditional review, this book got starred reviews at both the Hornbook and Kirkus. I’m going to take a look at the story from the perspective of cultural authenticity.

I’m a person of Irish descent who’s read a lot of Irish history. I read Irish writers regularly, play Irish music, and have a long involvement with the Irish music and dance community in the Pacific Northwest. I’m making an assumption that Mr. Curtis is not Irish, although many black people in North America do have some Irish heritage. Mr. Curtis didn’t mention his ethnic heritage in his bio or author’s note so I’m going to assume that he’s chosen to write outside of his personal cultural experience for the character Red.

The first thing I noticed in reading Red’s section of the book was that his voice sounded unlike any Irish person I know. Accent and turn of phrase is tricky, even when you know it well. Most readers would not be taken aback by Red’s word choices or turn of phrase, but I found them outside of my experience of the Irish. I also found a couple of idioms that sounded off to me. The phrase to twirl the cat, is unfamiliar but a similar phrase not room enough to swing a cat is one I’ve heard in several places and has a completely different connotation than the one Mr. Curtis refers to in the book. It would be easy to conclude that he’s guilty of lazy writing; HOWEVER, an idiom is a slippery thing, prone to multiple and regional meanings and inclined to change over time. In a story set a hundred years ago, it’s quite likely that the idiom I’m familiar with did not exist in its present form or had several meanings right from the start. Likewise the accent Mr. Curtis is portraying may well be one with which I’m unfamiliar. I speak regularly with people from Donegal, Clare, and Cork. I’ve recently been to Dublin. Accents differ in all four places and I’m sure there are accents I’m unfamiliar with. Even my extensive reading of Irish authors does not make me an expert of every Irish dialect. Other aspects of the book are well researched so I’m going to assume this accent was also based on appropriate readings and recordings.

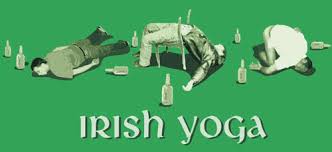

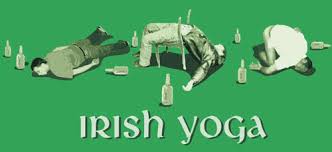

Characterization and cliche are another area of concern in the book. Though it is not in vogue to remember, racism has often be directed at white people. Try searching on the term “Irish” in an image directory and see what you get. Here are four things that turned up amid a sea of shamrocks on Google Image.

As you can see we get the unflattering sports mascot, the depiction of drunkenness, the quaint and pastoral people wearing green, and a display of domestic violence. These were among the top twenty-five images containing people. I decided to leave out the lewd Halloween costumes, the magical druids, the leprechauns, and the beer. For comparison take a look at what a google image search gives you for French or British or even African American. It’s a pretty striking difference. I don’t want to get into a debate about who has it worse in terms of mainstream depiction of their ethnicity. There are no winners in that game. Just making an observation.

The Madman of Piney Woods contains some cliches and overly broad characterizations of the Irish. None so egregious as the images above, but cliches none the less. The most obvious ones are Alvin’s red hair, domestic violence, the grandmother’s anger and bitterness, and the father’s too-good-to-be-true sagacity. So what to make of all that.

Red hair is rare, occurring in only about 4% of North Americans. Even in Ireland, only 10% of the population have red hair. It’s an easy way to telegraph Irish-ness without giving a more thoughtful and nuanced description–red hair is the feathered headdress of the Irish. On the other hand, further description would get into skin tone and comparative coloring to the black characters in the story and that’s a linguistic minefield. I’d probably make the same choice myself.

Domestic violence is a crime long associated with the Irish and I was sad to see that characterization repeated in this story. On the other hand, in 1901 the beating of children was more common among all races and classes of people, and not on anyone’s radar in the way it is today. And Mr. Curtis did not equate the violence with Irish-ness but clearly laid the blame on the ravanges of alcoholism or PTSD from a traumatic migration experience. It’s not “nice” but it’s fair and authentic to the period.

The dynamic between the saintly dad and evil grandmother was a bit over the top for my taste. Red’s father was very Atticus Finch-like in his goodness, and he was even in the legal profession. The grandmother’s bitterness also seemed a bit one-note to me. I’d have like to see a more developed version of this character. For example a woman in her position would have attended Mass as assiduously as she avoided the racist grocer. I found it odd to find so little mention of church. Most Irish of the era whether Catholic or Protestant had a lot of cultural identity and social support wrapped up in church-going. A view into that part of the Stockard family’s life might have made them all seem more rounded and realistic. That said, in many families with an abusive member, the other adult in the situation compensates for it with heroic kindness and a hard won wisdom about human nature.

And here are some things I found completely realistic and true to the Irish-American experience.

The connection between Irish and African music is longstanding, and in my opinion, a great benefit to the cannon of North American music. When I hear Reggae, I hear a slow and soulful version of the traditional hornpipe. In Gospel music I find much in common with Irish ballads. Contemporary Irish music is full of influences that echo it’s development alongside African-American music That connection was beautifully portrayed in the climactic scene where Red sings to the Madman of Piney Woods. I found it the most moving portion of the book.

The racism towards Black Canadians by Grandmother O’Toole was also true to what I’ve heard and read about the Irish immigrant experience. Black freedmen and Irish immigrants were often scrambling for purchase on the lowest rung of the economic ladder which tended to put them in conflict. I wish the history were otherwise but it isn’t. I think the discomfort that the prejudice is likely to generate is ultimately helpful in terms of the conversations it might inspire about how fear and hatred arise.

And finally what I really loved about the story was its willingness to show in careful (but not overwhelming for a young reader) detail the horrors that many migrating Irish experienced. Our current experiences with Ebola provide a very striking parallel to the Irish who were quarantined on ships carrying Typhus. (What a terrific book discussion that could be!) The Irish immigration experience is not a story that comes into the school curriculum very often or very accurately. It’s seldom the subject of a kid’s book. I was very grateful to see it portrayed so sensitively here.

Ethnic diversity in children’s books matters and I’m thrilled that someone outside of the Irish writing community was willing to take on this topic and bring it to light with compassion. I’m happy to see that the book has been well-received by critics who might have quibbled over details of authenticity or who has the “right” to tell an Irish story. Details matter but intention matters too. I want lots more books with ethnically diverse characters, not just the few that can pass the narrow gate of some critic’s opinion of their authenticity. Because here is the most uncomfortable truth of all. Even though I’m of Irish heritage, it’s no guarantee that I would write a more “authentic” story. My experience of being Irish is specific and narrow. I have biases about my own history, and any writer working from their own heritage faces risks of censure from within their own community.

Sometimes the view of an outsider who is willing to do solid research and the hard work of empathy is just as valid and maybe even a bit more objective. Thank you Mr. Curtis for a thoughtful and bravely told tale.

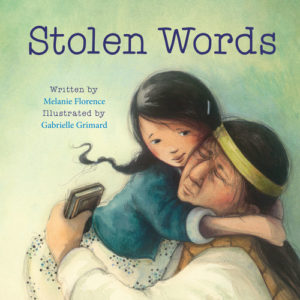

Writing about the ravages of colonial control over First Nations in the United States and Canada is difficult enough when addressing adults. It’s even more challenging when presenting material to the youngest readers. How to convey the seriousness and depth of pain without crushing the spirit of the child reader–it’s a huge challenge, and I admire any author who even attempts to take it on. Few come out with such a successful result as author Melanie Florence in her picture book Stolen Words about her grandfather’s forced enrollment in boarding school and the loss of his mother tongue. Ms. Florence tells the story of a young girl who innocently asks her grandfather how to say grandpa in Cree. He tells her about being taken away from home and punished at the boarding school for speaking his Cree language. Illustrator Gabrielle Grimard captures this beautifully representing the Cree language as a blackbird captured in a cage and locked away. It’s an image that conveys the sadness and brutality of the Canadian boarding school without presenting images too heart-breaking for young readers. The girl finds a Cree dictionary in her own school and brings it to her grandfather and the words on the page, again symbolically, take the fo

Writing about the ravages of colonial control over First Nations in the United States and Canada is difficult enough when addressing adults. It’s even more challenging when presenting material to the youngest readers. How to convey the seriousness and depth of pain without crushing the spirit of the child reader–it’s a huge challenge, and I admire any author who even attempts to take it on. Few come out with such a successful result as author Melanie Florence in her picture book Stolen Words about her grandfather’s forced enrollment in boarding school and the loss of his mother tongue. Ms. Florence tells the story of a young girl who innocently asks her grandfather how to say grandpa in Cree. He tells her about being taken away from home and punished at the boarding school for speaking his Cree language. Illustrator Gabrielle Grimard captures this beautifully representing the Cree language as a blackbird captured in a cage and locked away. It’s an image that conveys the sadness and brutality of the Canadian boarding school without presenting images too heart-breaking for young readers. The girl finds a Cree dictionary in her own school and brings it to her grandfather and the words on the page, again symbolically, take the fo rm of blackbirds and fly free. It’s a simple tale–too simple for older readers certainly who need much more substance and a less tidy resolution. But for the youngest readers this is an important story of native language denied and ultimately regained, and a book well worth celebrating.

rm of blackbirds and fly free. It’s a simple tale–too simple for older readers certainly who need much more substance and a less tidy resolution. But for the youngest readers this is an important story of native language denied and ultimately regained, and a book well worth celebrating.

A lot of the work of being an author is the dull and dry sitting at a desk (even when that desk is in a tree) and writing day after day. But every now and then an event comes along that you know you’ll remember forever. The American Indian Cultural Festival in The Dalles last week was just such a moment. It was a celebration of literature and poetry and music and dance. It involved a group of books that I admire and authors I feel honored to share the stage with: Elizabeth Woody, Oregon’s Poet Laureate, Craig Lesley, acclaimed author of contemporary western literature, and National Book Award winning writer Sherman Alexie.

A lot of the work of being an author is the dull and dry sitting at a desk (even when that desk is in a tree) and writing day after day. But every now and then an event comes along that you know you’ll remember forever. The American Indian Cultural Festival in The Dalles last week was just such a moment. It was a celebration of literature and poetry and music and dance. It involved a group of books that I admire and authors I feel honored to share the stage with: Elizabeth Woody, Oregon’s Poet Laureate, Craig Lesley, acclaimed author of contemporary western literature, and National Book Award winning writer Sherman Alexie. conjunction with the great booksellers at Oregon’s oldest bookstore Klindt’s who sold all the books and hosted many of the events. Tina Ontiveros is the manager at Klindt’s and Joaquin Perez is the owner. The fundraising for this event was truly a community affair with donations coming from area schools and libraries, educational foundations, local congregations, Oregon’s poet laureate program, the Wasco County Cultural Trust, the Ford Foundation, the Meyer Memorial Trust, and the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde. It’s inspiring to see so many community members come together in support of literacy and the cultural understanding of our local American Indian communities. Thank you!

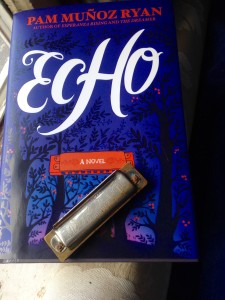

conjunction with the great booksellers at Oregon’s oldest bookstore Klindt’s who sold all the books and hosted many of the events. Tina Ontiveros is the manager at Klindt’s and Joaquin Perez is the owner. The fundraising for this event was truly a community affair with donations coming from area schools and libraries, educational foundations, local congregations, Oregon’s poet laureate program, the Wasco County Cultural Trust, the Ford Foundation, the Meyer Memorial Trust, and the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde. It’s inspiring to see so many community members come together in support of literacy and the cultural understanding of our local American Indian communities. Thank you! Lost and alone in a forbidden forest, Otto meets three mysterious sisters and suddenly finds himself entwined in a puzzling quest involving a prophecy, a promise, and a harmonica. Decades later, Friedrich in Germany, Mike in Pennsylvania, and Ivy in California each, in turn, become interwoven when the very same harmonica lands in their lives. All the children face daunting challenges: rescuing a father, protecting a brother, holding a family together. And ultimately, pulled by the invisible thread of destiny, their suspenseful solo stories converge in an orchestral crescendo.

Lost and alone in a forbidden forest, Otto meets three mysterious sisters and suddenly finds himself entwined in a puzzling quest involving a prophecy, a promise, and a harmonica. Decades later, Friedrich in Germany, Mike in Pennsylvania, and Ivy in California each, in turn, become interwoven when the very same harmonica lands in their lives. All the children face daunting challenges: rescuing a father, protecting a brother, holding a family together. And ultimately, pulled by the invisible thread of destiny, their suspenseful solo stories converge in an orchestral crescendo.

to edge it up to YA. This is the perfect book for that tender-hearted teenaged reader who is not interested in sexual relationships and blatant violence. It’s also great for that really young high level reader who needs a challenge and a story with substance but isn’t up for YA content.

to edge it up to YA. This is the perfect book for that tender-hearted teenaged reader who is not interested in sexual relationships and blatant violence. It’s also great for that really young high level reader who needs a challenge and a story with substance but isn’t up for YA content.