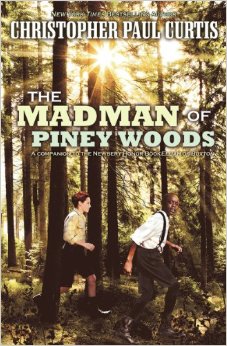

I read The Madman of Piney Woods, the latest book by Christopher Paul Curtis, this fall because I am working on a novel with two protagonists and I wanted to study how a real master of the craft handled the inherent difficulties in dual narration. But I become distracted from my initial goal by the story of Alvin “Red” Stockard. If you are looking for a more traditional review, this book got starred reviews at both the Hornbook and Kirkus. I’m going to take a look at the story from the perspective of cultural authenticity.

I read The Madman of Piney Woods, the latest book by Christopher Paul Curtis, this fall because I am working on a novel with two protagonists and I wanted to study how a real master of the craft handled the inherent difficulties in dual narration. But I become distracted from my initial goal by the story of Alvin “Red” Stockard. If you are looking for a more traditional review, this book got starred reviews at both the Hornbook and Kirkus. I’m going to take a look at the story from the perspective of cultural authenticity.

I’m a person of Irish descent who’s read a lot of Irish history. I read Irish writers regularly, play Irish music, and have a long involvement with the Irish music and dance community in the Pacific Northwest. I’m making an assumption that Mr. Curtis is not Irish, although many black people in North America do have some Irish heritage. Mr. Curtis didn’t mention his ethnic heritage in his bio or author’s note so I’m going to assume that he’s chosen to write outside of his personal cultural experience for the character Red.

The first thing I noticed in reading Red’s section of the book was that his voice sounded unlike any Irish person I know. Accent and turn of phrase is tricky, even when you know it well. Most readers would not be taken aback by Red’s word choices or turn of phrase, but I found them outside of my experience of the Irish. I also found a couple of idioms that sounded off to me. The phrase to twirl the cat, is unfamiliar but a similar phrase not room enough to swing a cat is one I’ve heard in several places and has a completely different connotation than the one Mr. Curtis refers to in the book. It would be easy to conclude that he’s guilty of lazy writing; HOWEVER, an idiom is a slippery thing, prone to multiple and regional meanings and inclined to change over time. In a story set a hundred years ago, it’s quite likely that the idiom I’m familiar with did not exist in its present form or had several meanings right from the start. Likewise the accent Mr. Curtis is portraying may well be one with which I’m unfamiliar. I speak regularly with people from Donegal, Clare, and Cork. I’ve recently been to Dublin. Accents differ in all four places and I’m sure there are accents I’m unfamiliar with. Even my extensive reading of Irish authors does not make me an expert of every Irish dialect. Other aspects of the book are well researched so I’m going to assume this accent was also based on appropriate readings and recordings.

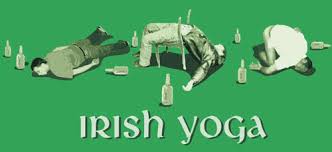

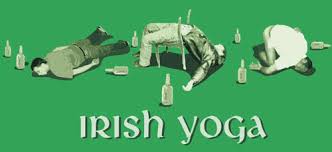

Characterization and cliche are another area of concern in the book. Though it is not in vogue to remember, racism has often be directed at white people. Try searching on the term “Irish” in an image directory and see what you get. Here are four things that turned up amid a sea of shamrocks on Google Image.

As you can see we get the unflattering sports mascot, the depiction of drunkenness, the quaint and pastoral people wearing green, and a display of domestic violence. These were among the top twenty-five images containing people. I decided to leave out the lewd Halloween costumes, the magical druids, the leprechauns, and the beer. For comparison take a look at what a google image search gives you for French or British or even African American. It’s a pretty striking difference. I don’t want to get into a debate about who has it worse in terms of mainstream depiction of their ethnicity. There are no winners in that game. Just making an observation.

The Madman of Piney Woods contains some cliches and overly broad characterizations of the Irish. None so egregious as the images above, but cliches none the less. The most obvious ones are Alvin’s red hair, domestic violence, the grandmother’s anger and bitterness, and the father’s too-good-to-be-true sagacity. So what to make of all that.

Red hair is rare, occurring in only about 4% of North Americans. Even in Ireland, only 10% of the population have red hair. It’s an easy way to telegraph Irish-ness without giving a more thoughtful and nuanced description–red hair is the feathered headdress of the Irish. On the other hand, further description would get into skin tone and comparative coloring to the black characters in the story and that’s a linguistic minefield. I’d probably make the same choice myself.

Domestic violence is a crime long associated with the Irish and I was sad to see that characterization repeated in this story. On the other hand, in 1901 the beating of children was more common among all races and classes of people, and not on anyone’s radar in the way it is today. And Mr. Curtis did not equate the violence with Irish-ness but clearly laid the blame on the ravanges of alcoholism or PTSD from a traumatic migration experience. It’s not “nice” but it’s fair and authentic to the period.

The dynamic between the saintly dad and evil grandmother was a bit over the top for my taste. Red’s father was very Atticus Finch-like in his goodness, and he was even in the legal profession. The grandmother’s bitterness also seemed a bit one-note to me. I’d have like to see a more developed version of this character. For example a woman in her position would have attended Mass as assiduously as she avoided the racist grocer. I found it odd to find so little mention of church. Most Irish of the era whether Catholic or Protestant had a lot of cultural identity and social support wrapped up in church-going. A view into that part of the Stockard family’s life might have made them all seem more rounded and realistic. That said, in many families with an abusive member, the other adult in the situation compensates for it with heroic kindness and a hard won wisdom about human nature.

And here are some things I found completely realistic and true to the Irish-American experience.

The connection between Irish and African music is longstanding, and in my opinion, a great benefit to the cannon of North American music. When I hear Reggae, I hear a slow and soulful version of the traditional hornpipe. In Gospel music I find much in common with Irish ballads. Contemporary Irish music is full of influences that echo it’s development alongside African-American music That connection was beautifully portrayed in the climactic scene where Red sings to the Madman of Piney Woods. I found it the most moving portion of the book.

The racism towards Black Canadians by Grandmother O’Toole was also true to what I’ve heard and read about the Irish immigrant experience. Black freedmen and Irish immigrants were often scrambling for purchase on the lowest rung of the economic ladder which tended to put them in conflict. I wish the history were otherwise but it isn’t. I think the discomfort that the prejudice is likely to generate is ultimately helpful in terms of the conversations it might inspire about how fear and hatred arise.

And finally what I really loved about the story was its willingness to show in careful (but not overwhelming for a young reader) detail the horrors that many migrating Irish experienced. Our current experiences with Ebola provide a very striking parallel to the Irish who were quarantined on ships carrying Typhus. (What a terrific book discussion that could be!) The Irish immigration experience is not a story that comes into the school curriculum very often or very accurately. It’s seldom the subject of a kid’s book. I was very grateful to see it portrayed so sensitively here.

Ethnic diversity in children’s books matters and I’m thrilled that someone outside of the Irish writing community was willing to take on this topic and bring it to light with compassion. I’m happy to see that the book has been well-received by critics who might have quibbled over details of authenticity or who has the “right” to tell an Irish story. Details matter but intention matters too. I want lots more books with ethnically diverse characters, not just the few that can pass the narrow gate of some critic’s opinion of their authenticity. Because here is the most uncomfortable truth of all. Even though I’m of Irish heritage, it’s no guarantee that I would write a more “authentic” story. My experience of being Irish is specific and narrow. I have biases about my own history, and any writer working from their own heritage faces risks of censure from within their own community.

Sometimes the view of an outsider who is willing to do solid research and the hard work of empathy is just as valid and maybe even a bit more objective. Thank you Mr. Curtis for a thoughtful and bravely told tale.

I’ve discovered to my delight a number of podcasts that offer regular discussion of all things writerly. I like to listen to them when I’ve got a long solo road trip or when I’m cooking dinner. I’m going to list three of my favorites in the hopes that you will help me find more.

I’ve discovered to my delight a number of podcasts that offer regular discussion of all things writerly. I like to listen to them when I’ve got a long solo road trip or when I’m cooking dinner. I’m going to list three of my favorites in the hopes that you will help me find more. The first podcast I became aware of is The Narrative Breakdown by Cheryl Klein and James Monohan. It is a blog focused on the craft of story making through the lens of fiction editor Cheryl Klein and script and screewriter James Monohan. They really go in depth on topics from scene construction to character development to the power of irony. You can find their website here or subscribe to them through iTunes.

The first podcast I became aware of is The Narrative Breakdown by Cheryl Klein and James Monohan. It is a blog focused on the craft of story making through the lens of fiction editor Cheryl Klein and script and screewriter James Monohan. They really go in depth on topics from scene construction to character development to the power of irony. You can find their website here or subscribe to them through iTunes. I should say at the outset that my godparents got me a book of O. Henry’s short stories for my 10th birthday and I’ve been a fan of short stories ever since. This podcast is hosted by the editor of the New Yorker. She invites a different New Yorker story writer to choose a story from the archive and read it aloud. Then they discuss what makes the story special. Though none of the stories in the New Yorker are for children, I’ve learned a lot and broadened my scope considerably.

I should say at the outset that my godparents got me a book of O. Henry’s short stories for my 10th birthday and I’ve been a fan of short stories ever since. This podcast is hosted by the editor of the New Yorker. She invites a different New Yorker story writer to choose a story from the archive and read it aloud. Then they discuss what makes the story special. Though none of the stories in the New Yorker are for children, I’ve learned a lot and broadened my scope considerably. The third podcast I listen to regularly is more of a fan thing. I’ve been a reader of Sherman Alexie’s work for decades before he wrote for children. He’s a very engaging speaker and I’ve heard him in person a dozen times at least so when I heard he has a podcast, I subscribed immediately. The podcast is called A Tiny Sense of Accomplishment and it’s an ongoing conversation with fellow writer and small town Washington boy Jess Walters. The conversations they have range widely but are fascinating and revolve around all the various aspects of the writers life with the occasional foray into basketball and middle aged angst.

The third podcast I listen to regularly is more of a fan thing. I’ve been a reader of Sherman Alexie’s work for decades before he wrote for children. He’s a very engaging speaker and I’ve heard him in person a dozen times at least so when I heard he has a podcast, I subscribed immediately. The podcast is called A Tiny Sense of Accomplishment and it’s an ongoing conversation with fellow writer and small town Washington boy Jess Walters. The conversations they have range widely but are fascinating and revolve around all the various aspects of the writers life with the occasional foray into basketball and middle aged angst.